Gina writes:

On Saturday, I had the last-minute opportunity to go on a field visit, accompanying an external evaluator to hear about the impact of SPREAD's programs from the perspective of the villagers. The evaluator turned out to be an American with decades of experience living and working in countries all over Africa, Asia, and South America, so it was interesting to hear about his life. I was more interested though, to soak in the experience of being out in the villages for what I knew would be the last time. We leave Koraput on Sunday morning!

Even on the 2+ hour drive to the field area, I had to fight back a tiny tear, thinking about the vistas that I'm leaving behind.

Both villages that we visited had been told that this visit was extremely important to the continuation of SPREAD's programs in the area, so the welcome was extra-special, with garlands of flowers, turmeric and seeds thumbed on our foreheads, and drums and dancing.

When the villagers crowded around to discuss SPREAD's activities, I realized that it was possibly the last time in my life when I'd be able to quietly observe the dynamics of village life in rural India.

In the first village, the women and men were separated into two groups and I sat with the women's group while the evaluator asked questions through a translator. Since the women don't talk much if there's only one group, it was interesting to hear how SPREAD's activities have affected their lives directly. The translations made for slow going though, so I had ample time to take in the small details that I love about village life.

Boys with their arms wrapped around each other, love it!

A small baby enthralled with a tiny goat.

Boys playing on a bike.

We visited two villages where the whole village came together to discuss SPREAD's impact. Between those visits, we went to Kajuripadar, where SPREAD has a field office that I've visited before. There was a women's group meeting taking place there, with women from 10 different villages. The evaluator asked some questions about the operation of the group.

After the translated questions was the most heart-wrenching part of the day. Malti, who is the president of the entire women's group, is a tribal woman who lives in Kajuripadar and has led the group to do amazing things to fight for forest rights, ban liquor, and more. A few months ago she was in the SPREAD office and, somehow, we ended up really connecting. I was just using my basic Oriya and she was just laughing at my pronunciation, but it was the first time that I'd had the opportunity to spend time one-on-one with a tribal person without them feeling extremely shy and me feeling extremely awkward. It's hard to explain, but her caring and lighthearted nature came across in that hour sitting outside the office. I saw her again a few days later and we made tentative plans for me to visit the village again, since SPREAD has a field office there. With winding up work at SPREAD, however, there wasn't time. So I was ecstatic to know that we'd be dropping in to Kajuripadar.

After the meeting, I asked if I could have a picture taken with her. She happily agreed.

Tribal women are small!

Then the rest of the women's group wanted a picture with me, which made me so happy. I love this picture!

I wish I'd met Malti earlier in my time here in Koraput, but even the small connection that we had is something I will always cherish. Seeing her again and sitting in the midst of these amazing women really did make me catch my breath, because I know that the closest I will ever come to being "one of them" is right now. I of course will always be an outsider even if I visit later in life, but after two years of practicing Oriya, making field visits, staying in their villages, and building relationships with the SPREAD staff so that they know they can trust me, I feel comfortable sitting in a village with these people and they feel more at ease with me.

People have been asking us a lot lately when we'll come back to Koraput. The answer that we've taken to giving is, "Sure, in 5 or 10 years, we'll come and we'll bring our children." Whether it's the response that we've settled on for ease of answering or it's a true prediction, only time will tell.

Labels: Work

Gina writes:

While here in India, I've done some web design and print design projects for the 2 NGOs that I've worked for (SOVA and SPREAD) as well as for a few other NGOs that have VSO volunteers. When fellow volunteer Sheila asked me if I would consider redesigning the website for Shakti, the organization that she works for, I was confident that I could use what I've learned in the past 2 years to manage the project efficiently and with minimal frustration.

There were aspects that highlighted the specific considerations necessary when working across cultures:

- Working for free - Based on a negative past experience when working for free, I knew how important it was to clearly define the scope of the work and to be firm about limiting request after request after request for "one last change". I developed various decision points or "gates" after which no changes could be made -- the template was chosen, then look and feel was customized, then navigation was finalized, then content was provided. I was flexible to some extent, but Shakti understood and respected that requests for changes after the "gate was closed" were limited.

- Working via email - Communicating primarily online is not a preferred method of working for most Indians, who greatly value the personal relationship and face-to-face contact. Fortunately, Sheila was at Shakti helping to manage the project from that end and vouching for my expertise. She and her boss also made the 4-hour trip to Koraput in July, which helped her boss to trust me more and showed me they were serious about the project.

- Designing for Western and Eastern - The website has varied audiences: other Indian NGOs and international funding organisations. The Indians expect lots of color and don't mind flashing, moving elements. Western viewers prefer more subdued, polished sites. It was interesting to keep both sets of expectations in mind when determining the look and feel. I also had to be firm in my declarations of what was "best practice" in responding to some requests from the boss.

- Training - Part of the project was a visit to Shakti to conduct updating/maintenance training for the staff. I really enjoyed developing the training materials, trying to meet the needs of 3 people with varying levels of English comprehension and very little knowledge of HTML and basic web design principles. I was proud of what I developed and of my delivery, remembering to speak simply and slowly and check often for comprehension.

- Free, off-line tools - It goes without saying that Shakti cannot afford to purchase expensive web design software like Dreamweaver. They also are determined not to use the widely-available pirated software, which is respectable. Thus, I needed to find a tool for them to make changes that was free (or very cheap) and easy to use. It also needed to allow for editing off-line, as Shakti's power/Internet situation is extremely unstable. I spent a lot of time evaluating different options and found one that really impressed me.

The goal for a "go-live" date for the website was early September. Of course that deadline is long past. Even so, the site is well on its way to completion.

I was in Rayagada for 2 days this week training the team and was very pleased with their understanding of the concepts. To Shakti staff, thanks for being great students and welcomings hosts. Now I just hope we can get it to a public-ready state in the next 9 days before I leave!

Labels: Work

Corey writes:

Last week my VSO Programme Manager, Praveen, came to visit Koraput. He was here to do my final review and to check up on the progress of the SAMADHAN project. He was also here to make a field visit and he asked me to come along. More about that later.

Praveen arrived on Thursday and we spent an hour catching up. We haven’t seen each other since June and he just returned from a month trip to Kenya and Canada. It was interesting talking to him about some of the differences between North America and India. Praveen is also very knowledgeable of development in India so I like to pick his brain about different topics.

One of the topics that has been debated in the press and government recently is the upcoming BPL survey. BPL stands for Below the Poverty Line. Basically the Indian government is responsible for surveying the population and identifying which households are BPL (poor). Once your household is identified as BPL you are then entitled to a number of social security plans, including subsidized rice, flour, and kerosene. If you are interested to learn more, you can check out the Wikipedia page.

There are many reasons why this is a hotly contested issue. Citizens and NGOs want to widen the social safety net and make sure that no one that is poor is left out. The government wants to limit the social safety net and maximize the tax revenues left over for investment in other areas like public works, education, defense, etc.

As a development professional, Praveen is concerned that the proposed criteria for the next survey will exclude many families with disabled people in them. He wanted to interview some families with disabled members living in Koraput and to find out the real costs associated with supporting a disabled family member in rural India. Towards that goal, we set out at 8am on Friday to Bandaguda, a village about 20 km from Koraput town.

We arrived at the village along with some staff from Ekta, another local VSO partner. Praveen and the Ekta staff sat down at the first households to interview the first family. It consisted of three members: a daughter, a mother, and a grandmother. Domni, the daughter has multiple disabilities and is totally dependent on a caretaker. In addition, the family’s earning ability is really curtailed without an adult male member. So the mother, 40, and the grandmother, 65, have to do manual labour to support the family. Every time Domni needs to go to the hospital, the mother and grandmother have to forgo a day of wages and spend about 600 rupees in transportation and medicine. They have spent around 10,000 rupees over the last ten years caring for Domni. But because there are non-disabled adult members of the family they are not considered BPL.

Next we went to another part of the same village and interview two more families. Both were in similar financial straits to Domni’s family. The first included Mitun, a young boy with multiple disabilities. His family is a little better off as his father can work and earns about 2000 rupees per month. However, the family took a loan of 10,000 rupees to pay for treatment for Mitun and are still repaying this loan. The last household has three brothers and a father, the mother recently died. Two of the brothers were disabled which meant that the third brother and the father had to forgo work or school to care for them. They have also taken on a loan of 20,000 rupees at 10% interest. These last two families are also not counted as poor under the latest iteration of the BPL criteria.

As always, I liked the chance to get out into the field and do some work. This will probably be my last time. I hope that Praveen is successful in his efforts to revise the BPL criteria so that these families and others like them will get some help.

Labels: Work

Gina writes:

When I go on field visits, I get to observe tribal culture and customs in a way that never comes across in my photographs. That's because my personal "code of ethics" regarding photography is fairly strict; I don't often take pictures of the villagers for fear of offending them and using them for my own gains without giving anything back.

The SPREAD staff, however, are in a different position. They speak the language of the villagers, they've built rapport and gained trust, and the villagers can specify how the staff member has helped them (hopefully!). Thus, the following photographs, taken by my coworkers, can do what mine cannot -- give you a glimpse into what I see when I visit the field.

First, the tribal women. Each tribe has certain jewelry, clothing and/or tattoos that signify their tribe.

(The camera is not part of her tribe's accessories, but it looks cool!)

The tribal men often wear Western-style shirts and just a wrapped cloth around their hips instead of pants.

ALL Indians have the ability to squat for hours on end. With their feet flat on the ground, it's not uncomfortable for them at all and is their preferred position of rest.

This picture of villagers waiting to pick up their subsidized rice shows a few interesting things. First, see how tightly they're packed into that line! This was taken in May, so it was likely more than 100 degrees. Second, see how there is a line for men and a line for women.

This picture is the best one I have that shows what typical village looks like.

All around Koraput, you can see women carrying jugs of water on their heads. They start practicing when they're little girls, with small cups of water. It's cute and sad.

This picture is interesting to me because it shows the reality of the village kids. They take awhile to warm up and start smiling and laughing and sometimes never do. Oftentimes, they're just confused about strangers coming to their village. Also, Indians don't usually smile for photographs, so smiles are more common in candid shots.

A village meeting will either take place on the cement platform that is in almost every village for just this purpose or in the school. A meeting is a good chance to see the Indians' different definition of "personal space". They crowd into the space even if there is plenty of room, very interesting.

Having the chance these past 2 years to spend time with these people, even just in observation, has been amazing. Thanks to my coworkers, I now have some better pictures to remember it by!

Labels: Indian Culture, Work

Gina writes:

Yesterday was SPREAD Foundation Day. 22 years ago, Bidyut signed the papers (or something) and the dream that he and his friends had to start an organization to help Koraput's rural poor was realized. To celebrate this day, SPREAD invites all of the staff to a celebration.

In the afternoon, staff began arriving. The office was filled with chatter and commotion, which in all honesty, just made me feel lonely, working in my office, wishing I could speak better Oriya. I wanted to join in and help, but my presence sometimes makes the field staff, who speak no English, uncomfortable. Eventually, all the staff gathered in a circle and started peeling garlic and onions and cutting gargantuan amounts of vegetables.

I joined in and kinda sorta mixed in with the group. My pitiful Oriya is always a good ice-breaker.

A few hours later (notice how our sense of time has changed? a few hours of waiting around is no big deal...), pretty much everyone was there. We gathered in a tight circle around a bright pink cake and talked about SPREAD.

I only caught the gist of the conversation, but the long-time workers were recognized for their service and people shared their memories of their first day at SPREAD. Even though I couldn't understand the specific words, it was cool to know that the whole room was thinking about SPREAD as an organization and what it means to them.

After story time, the cake was cut. In accordance with Indian tradition, certain people (the kids, in this case) fed cake to each other. I was wondering how they were going to efficiently distribute cake to the 50+ people crowded in the room, but I shouldn't have worried. Hands dived in from all sides, pieces were passed around to those standing on the outskirts (me), and the cake was demolished in under a minute!

Then there was the obligatory cake fight, which I did not participate in. :)

After finishing the cake, we sat down again and Bidyut discussed SPREAD's proud accomplishment from last week. Almost a year ago, 9 boys aged 11-16 were lured to migration work in Pune. After working 16-20 hours per day for many months, the contractor stopped feeding the boys and was killed as a result. After 1 boy escaped and travelled back to Koraput, SPREAD worked with other NGOs and officials to locate the boys, get them a fair sentence, and transport them back to Orissa. As of last week, all 9 boys are safe at home!

Then I was invited to speak about my experience at SPREAD. I was not prepared to speak and am not used to speaking with an interpreter, so it was awkward. But I managed to convey my gratitude to SPREAD for treating me as one of their own rather than a VIP, express my belief that I've gained more from them than they have from me, and invite them to contact me for any help via email in the future. It was sweet and sad at the same time, sort of a good-bye for me.

Soon after that, dinner was ready. It was as delicious as expected, complete with kheer (Indian rice pudding)! When I finished eating, I realized that it was after 10 p.m.! My landlord was upset that I hadn't called him to let him know that I'd be late (oh India), so I hopped a ride home on a co-workers motorbike right away.

Happy birthday, SPREAD! Here's to 22 more years!

Labels: Work

Gina writes:

Yesterday was a holiday to honor Ganesh, the elephant-headed god of knowledge and remover of obstacles. He's one of the head gods in Hinduism.

SPREAD celebrated this holiday with a puja (religious ritual of blessing) in the office. I had witnessed this once before, for a holiday in January, but was excited for Corey to attend his first office puja.

We arrived at about noon for the 11:30ish puja. Just before 3 p.m. the priest finally showed up! Apparently, he's in high demand on festival days, rushing from one engagement to the next. We had to wait until after the puja to eat lunch, so the rituals got underway immediately.

All of the specific items were prepared and ready for the puja - milk with honey, sandalwood, certain leaves, colored powders, a squared mound of dirt, coconuts, fruits and sweets, and of course the Ganesh idol/statue. Bidyut, SPREAD's director, was dressed in traditional silk robes to perform the puja. The priest chanted and sang specific verses, while cuing Bidyut to perform actions at the right times.

After about 15 minutes, my favorite part began. They built a fire right in the middle of the office! It got pretty big at one point.

The fire itself was not a problem, since the floors are concrete and their aren't curtains or anything to catch on fire. However, the room became extremely smoky after about 10 minutes and it was really irritating to the eyes.

The entire puja only took 1 hour, the perfect length! Here is the area after the rituals.

We finally got to eat at 4 p.m. The food was pure veg, which means no onion and no garlic, but at the same time, was richer because of the use of ghee (clarified butter).

I love this part of Indian work culture, because it's so different from Western ways. Imagine sitting down with your coworkers to perform a traditional ritual to bless your office space, books, computers, etc.!

One last picture: a colleague's son, dressed in traditional Oriya garments of his very own size! So cute!

Labels: Indian Culture, Work

Gina writes:

Frustration has been building regarding this issue and it's time for a rant about it. I'll try to be sensitive and honest at the same time, as usual, but I apologize in advance to any that I offend. The idea that has been keeping me up at night when I allow myself to think about it too much is this: funders expect very little from the NGOs that they fund and the result is a far lower level of impact than is possible.

For many Indian NGOs, the situation is this:

- the NGOs are funded by various international or national agencies (e.g. WorldVision, Save the Children, CARE)

- these funders provide money for specific activities (e.g. training sessions, running a residential school, providing goats for poor villagers) or sometimes for a general aim (e.g. raising awareness about government programs, increased possession of land titles, improved quality of education at the government primary schools)

- the NGOs complete the activities and report the results to the funders based on the funders' requirements (e.g. quarterly or semi-annual reports, specific templates requesting numbers data, stories of success and statements about change)

- the NGO submit the reports on time and with no red flags regarding misuse of funds or lack of action and the funder renews the project for another 2-4 years

After partially understanding this system and reading some general analyses of international development, I thought that potential problems with this system were:

- the funders expect very specific data regarding the impact (i.e. how the NGO's activities had changed people's lives for the better), which is difficult because a) long-term outcomes sometimes aren't evident until years after the activities take place and b) activities completed are much easier to measure than the change resulting from those activities

- the funders templates for reporting relied on development models called logistical frameworks or log-frames that are difficult to truly understand and apply to the work at hand

However, now after working with and observing the front-line level of international development (meaning the field workers who actually interact with the villagers and their managers who compile the data and write reports), I've come to a far different and upsetting conclusion -- funders expect very little from the NGOs that they fund and the result is a far lower level of impact than is possible. The funders don't actually seem to care if the reports are well-done, capturing impact and displaying an understanding of why the activities make sense. My reading lately has discussed funders' increased focus on evaluation and impact, but I don't see it. Almost all of the reports that I've seen over the past 20 months do not really convey how people's lives are better as result of the NGO's work. This lack of accountability for the NGO has drastic consequences:

- the NGO staff have no incentive to think about the impact of their activities; they just keep doing what they've been doing for years and assuming that the villagers will have better lives because of their work

- the NGO staff have no incentive to think about whether X or Y activity makes the MOST sense, given the cost and given the expected impact

- the NGO has no reason to work extra-hard to reach MORE beneficiaries; there are rarely expectations regarding specific numbers/goals (e.g. attending 70 village-level meetings per quarter, helping villagers to fill out 100 applications for new pensions per year)

- there is never (that I have seen or can imagine) an overall evaluation of the work the NGO is doing in particular villages, asking how the residents' lives have improved because of X activities over Y time period costing Z money

- 28 villages were sensitized on their rights to food

- 55 village women's committees met monthly and discussed things like drinking water and land rights

- community tracking of PDS (subsidized food program) is going on in all 75 villages

- 20 people attended the national convention on Right to Education

- how many people were "sensitized" on food rights and how can you measure their increased understanding? what will/did they do with this new knowledge?

- what changes have resulted from the formation of women's committees in the villages? do the committee members feel more confident as part of the committee? are there any unforeseen negative consequences from an approach focussing on forming MANY committees?

- what information was gained from the tracking of PDS? how was this information used to affect change? what was the NGO's role?

- what was the perceived benefit of the attendees to this convention? is this the MOST effective way to spend that amount of money?

It's easy to come down hard on the Indian NGOs. "Why don't they care more about the people they're serving?" "Why don't they want to do AS MUCH as they can to help AS MANY people as possible?" It's not that simple, though.

- The NGO staff at the bottom, the field workers (and even the project managers compiling the reports) get paid a tiny amount, barely enough to support a small family. Why should they provide anything but the bare minimum?

- NGO management is more often trained in development concepts and not leadership or personnel management concepts. It's difficult to expect them to know how to motivate their 50 staff working on their own out in the field.

- Low-quality reports have been accepted without question for years, so why should NGOs work to improve them?

- I'm hesitant to say this, but most Indians that I've met here in rural India do have a deficiency when it comes to analytical skills and critical thinking. The Indian education methodology doesn't encourage creativity or problem-solving, but focuses on rote memorization and knowledge of facts. So project managers, even with a degree in development studies or something similiar, often have difficulty thinking about the IMPACT of activities that their project completes, not too mention how to measure that.

So there you have it. I can't sleep because even my realist ideas of development were too optimisic. I think many Indian NGOs, including the 2 that I've worked with, ARE doing good work. But I don't think they're considering whether the activities that they've been doing for more than a decade truly make the MOST sense (or any sense) and I don't think the field staff are challenged to put their best effort into reaching as many people as possible.

I understand that development is hard. It's hard to do, it's hard to measure, it's hard to keep going. But there must be SOME way that the system can change to result in more impact and better use of funds. What that way is, I don't know. If you have any ideas, let me know, I could really use some encouragement...

Labels: Work

Gina writes:

Multiple choice quiz: What does capacity-building mean?

- I have no clue, but I use it all the time because I work in development and using it makes me look smrt.

- Something about teaching a man to fish instead of sharing your fish with him.

- An ongoing, iterative process whereby individuals, groups, organizations and societies enhance their ability to identify and meet development challenges by coordinating their efforts through participatory facilitation.

I think 3 might technically be right, but I can't quite get past the bullshit to see! 2 is a simplified version of the definition. Yes, capacity-building is the act of teaching someone HOW to do something rather than to do it for them. In the development world, this is like the Holy Grail of project planning.

It's been on my mind lately and I thought my ramblings might be of interest to some of this blog's audiences.

Capacity-building is one of VSO's key approaches to placements. We volunteers are trained to concentrate on transferring our skills to our coworkers in the partner NGO. This is why you don't see Corey and I out in the field very often; except for needing to understand the work that's done outside of the office (and wanting to be out there experienceing amazing stuff), there's not much that we can do out there to help our coworkers become better at their jobs. Though it's not as exciting, it's more useful for us to help in the office with report-writing skills, computer knowledge, and other things that affect future funding and the organization's ability to do and show their good work (and make the individuals themselves better development workers, for any future NGO they work at).

When you start work at an Indian NGO, however, it's difficult to get started building capacity immediately, telling people what they need to change and why. Especially as a younger person (both Corey and I) and as a woman (me, of course!), there's a relationship-formation process that has to happen before any foreigner can be critical and fill the role of "trainer". The key "ingredient" to speeding up this acceptance or even seeing it happen at all is the support shown to the volunteer by the NGO's director (called the "secretary" here). For my first year, the director did not publicly convey his belief in my skills, so capacity-building was next to impossible. When I left and started working at SPREAD instead, the director showed subtle signs of approval that the staff picked up on from the first day. It wasn't long before they started to come to me with questions.

Just yesterday was a small but meaningful victory for me. My coworker Prasant had asked me, on his own initiative, to develop a "documentation improvement plan" for him. I wrote some tips on how to ensure better English and better organization in his reports and how to include more relevant and useful data. When I sat with him yesterday to go over it in detail, he called in another staff member who is at an equivalent position (project manager) and also submits English reports to funders. Ajaya came into my office and the three of us ended up having a full hour, almost uninterrupted impromptu report training! It felt great to know that they respected my knowledge and were taking the time to gain skills from me. Small wins here in India...

Here's a "dramatic reenactment" of me training Prasant. It was taking today and not yesterday, but that really is how things work; people just sit with me at my desk and we work on my laptop on reports.

I'll mention that capacity-building is a "goal" for VSO volunteers, but that it's rarely possible to have a placement with 100% capacity-building activity. Usually there's a project or two that a volunteer does mostly indepently, like designing a website, developing templates, or developing a database to track information. These projects help to form the relationship that's necessary for capacity-building. They also fill a gap in the organization, because no one at the NGO has the skills to do it and hiring an external consultant it too expensive. And they provide long-time value for the organization.

What we volunteers try NOT to do too much of is provide direct service delivery, like writing proposal and reports (me) or fixing computers (Corey). Since we won't be around forever, we're supposed to train someone at the office to do it, connect the office with a capable service provider (i.e. computer repair shop), or just accept that the English or design might not be the same level that we could produce, but that's it's at least truly coming from the permanent staff.

The concept of capacity-building isn't that profound, but it's an idea that we keep in mind whenever we face a task. Is there a way to integrate some training in this task? What skills can I teach the people around me that will make them better at their jobs for years to come?

Gina writes:

Indians ask us about the U.S. pretty regularly. What is the climate like? Is there rice in America? America doesn't have poor people, right? Does everyone in America own a gun? What do American houses look like? Does everyone have a driver's license? Do you know Michael Jackson? (I didn't tell that kid that MJ was dead...) The stereotypes are usually based on what they've seen on TV.

A few months ago, though, I was faced with a really interesting situation. I was on a multi-day field visit with some SPREAD staff visiting a village to hear about their land rights work over the past few years. I had the rare chance to ask the 20 or so men a lot of questions about their work and their results, since I was in the de facto "reporter" position for SPREAD, gathering data for a document about land rights work. Due to that role and to me saying a few simple phrases in Oriya, I had built some rapport with them by the end of the hour long conversation (which of course was done by interpreter). The leader of the group then shyly asked the interpreter, "What is it like in her country?"

I realized the importance of my answer immediately. Not to tout my importance or anything, but this village knew NOTHING about the U.S. (no electricity means no TVs) except for the most general of stereotypes (Americans are rude, there is no poverty, they don't wear enough clothing), so my answer would probably be all they ever learned about my country. I wanted to tell them things that were interesting, but true, painted an accurate picture and maybe broke down some stereotypes. Since coming to India, I've realized more than ever how unfair it is to make generalizations about an entire large country. (I've also realized that I totally overthink EVERYTHING...oh well!)

What would you have said? How would you describe the U.S. in a few simple sentences?

Here's what I said:

- parents and married children don't live in the same house (showing a contrast to the joint families commonplace in India)

- all marriages are love marriages (as opposed to the majority of marriages in India, which are arranged)

- women often work outside of the home, even after they have babies

- we eat many many different types of food--rice, curries, sandwiches, Chinese, pasta (trying to say that we eat rice but also a vast variety of foods, also knowing they would not understand the concepts of Italian, Mexican, or European food)

- there is no caste, all are equal (maybe a bit idealistic, but a good statement to make to people constantly harrassed because of their caste/tribe)

- not all are rich, there are people without homes and without enough food to eat

- in the North, it is SO cold, even -15 or -20 [Celsius] (I've said this one to many Indians, it's guaranteed to get a shocked reaction and make them think that maybe America is less than perfect in just that one way)

Labels: Work

Gina writes:

Last week, I spent 3 days working in a rural area about 3 hours away from Koraput town. Our "home base" for the trip was one of SPREAD's field centres, 2 thatched roof buildings in a non-electrified village of 30 households.

I was accompanying my boss' wife on some work that she was doing and 3 of the program managers that I'm friends with were conducting meetings or doing field work in the area, so it was a lively group of people that I'm comfortable with and that speak good English.

Here's my friend Prasant. He was just trying to shield his skin from the sun, but I couldn't help laughing at his Unabomber-esque look!

The main purpose for our visit was to document the land titling process that SPREAD follows in helping villages to apply for and secure the appropriate land titles for their land. (Context: A vast majority of villagers in Koraput farm small patches of land, but don't actually own it. In some cases, they pay "rent" for the land and in some cases, they're just vulnerable to exploitation.) It was decided to visit the same village multiple times over the course of a few days, to document the process in-depth for one village, to be used for distribution to other NGOs who want to start similar land projects. (To clarify, this land project is not the same as the GPS/GIS work that I've been working on, which concentrates on villages that do not yet have cadastral maps to visualize their plots, but I was able to test the GPS device and some other things in actual field conditions, which was helpful.)

Visit #1

Our visit to Khajuriput on Tuesday morning was a meeting of a few hours where the SPREAD staff just asked questions about the process, which steps were taken, which steps were valuable, etc. I didn't follow the conversation at all, since it was in Oriya, but it was interesting to observe the behavior of the villagers. They were obviously quite proud of the work that had been accomplished and were very careful with the maps and documents. I could tell they were extremely important pieces of paper.

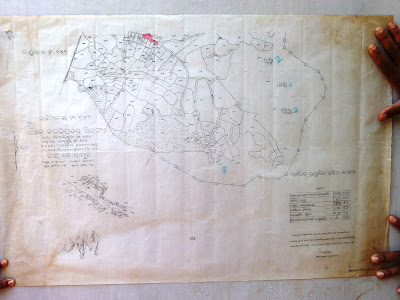

Here, some of the villagers are explaining the features of the cadastral map.

Break Time

The temperature was more than 100 degrees, which made us all exhausted by mid-day. We returned to the field centre about 10 minutes away from Khajuriput. The buildings were way too hot to spend much time in, so after lunch there were at least 3 people, including me, sacked out on the ground in the shade of a huge mango tree!

An air-conditioned room isn't missed so much when you get to nap in the shade with a breeze washing over you, hearing the chickens cluck and the cows moo to lull you to sleep.

Visit #2

At about 4:30, we returned to Khajuriput. This time, the villagers demonstrated their knowledge of chain surveying, the method of measurement that they learned when the professional surveyors came to make the cadastral map more than 20 years ago! I needed to take pictures of the process and wanted to test the GPS device out in the farm plots, so I headed out with 10 or so village men to the village boundary.

I always chuckle to myself in these situations, the tall white girl traipsing about the fields with a bunch of tribal men. I also enjoy smashing their stereotypes of foreigners. For instance, they were waiting at the vehicle for the driver to take us to the boundary point. I said (in Oriya, by the way), "How many kilometers?...One?...Oh, it's fine, let's go, no problem." And off we went to walk for a whole 10 minutes!

This man is a village leader of some sort. He was showing us how they measure distance/area with the chain (each link is 8 inches, 100 links is 66 feet, one acre is 10 chains by 1 chain).

I was excited to find certain places on the cadastral map and then mark them with the GPS device. Here is the cadastral map of the village, by the way.

I asked the men to lead me around the boundary of one entire plot, so that I could track it with the GPS device, to test for accuracy and usability. Here we are comparing the cadastral map to the actual land cover.

In this instance, I was so happy to have legitimate work that I was doing along with the villagers, as opposed to just observing and documenting, like I usually do.

Visit #3

The next afternoon, we visited Khajuriput again. They were creating an updated version of their village's social map. The original version was created 2 years ago, when SPREAD first starting working on land issues with them.

It shows each household and then tracks certain characteristics. Social maps often track health status or education, but in this case, tracked land issues. The different symbols mark the type of land that the household farms, whether the title is in possession, and other measures.

Watching the creation of the updated version was fascinating. The entire village came together to draw the houses and roads on the ground with rice powder and reddish dirt.

Then they chose different natural items like baby jackfruit, seeds, and leaves to mark the updated status.

After the map was completed, they could better visualize the progress that has been made in the last 2 years. SPREAD makes sure to emphasize that most of the progress is because of the village's initiative, not SPREAD's assistance. Really a cool process to watch!

Gupteswar

There was some information that we were waiting for from the SPREAD staff that work in the area, so we had to stay in the field center for an extra night. That meant that we could go to Gupteswar only 12 km away! Gupteswar is a Hindu temple that's in a cave, one of the popular tourist spots of Koraput district. Corey and I had wanted to go, but never had the chance. To be honest, the temple itself wasn't that impressive, just a series of small shrines in a cave that wound downward for about 300 feet. What was more impressive to me was the river area just down the hill from the temple. Beautiful! And we were there at the perfect time for an absolutely stunning picture.

I returned to Koraput exhausted but fulfilled. When do we go again?!

Labels: Work